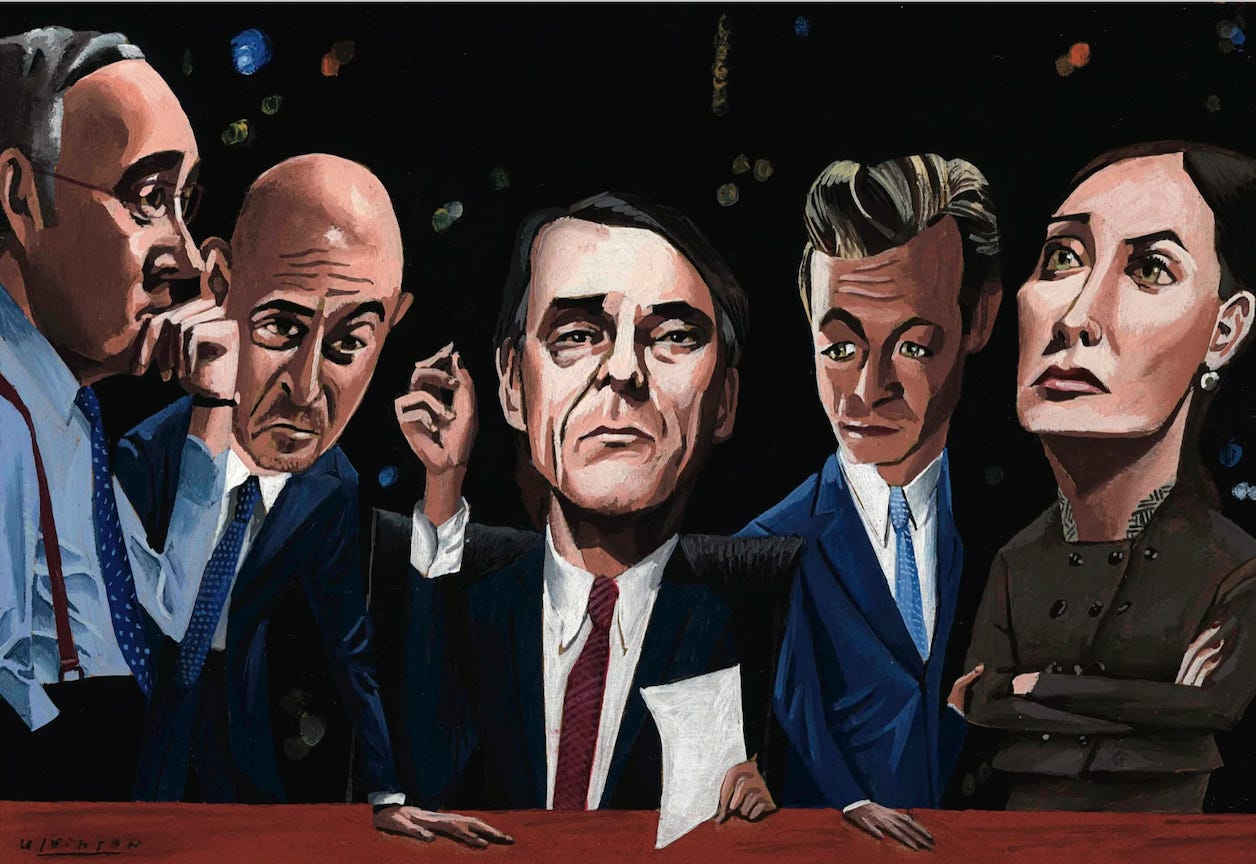

(Illustration by Mark Ulriksen for The New Yorker)

“Margin Call” begins with a gloomy overcast and a layoff. 80% of the staff at an elite investment bank are set to be let go. Eric Dale (Stanley Tucci), a risk manager, is laid off by two nameless women from an outside consulting firm. A former civil engineer, he’s been working there for 19 years. The junior of the two women attempts to be empathetic about the situation, giving well-intentioned platitudes about unexpected life changes that nevertheless come off as patronizing. The older, seasoned consultant delivers the news straight knowing the action will always be impersonal and a betrayal of his company loyalty regardless of the delivery.

After the layoffs are finished, the floor manager Sam Rogers (Kevin Spacey) gathers the remaining dispirited workers for a speech. Rather than offering consolations, he triumphantly congratulated them for being the select few remaining and trumpets the opportunity for ascending the company ranks that the departures have opened up.

This opening scene sets the tone of the film. Sentiments of morality, fidelity, or camaraderie are spurned by the competitive expectations of the firm which controls individuals through compensation packages, bonuses, and promotions. The most successful senior employees succeed by embracing the culture, whereas the junior employees fret about company loyalty and bereave the loss of their coworkers.

"Margin Call” tells the story of an investment bank on the precipice of the 2008 financial crisis. On discovery that their mortgage backed assets are worthless, over the course of the night they decide to front-run the forthcoming housing market collapse by dumping the assets and thereby triggering the collapse themselves. The film functions similarly to a heist film. The crew is assembled in the first half followed by a tense high-wire second act with suspense building until they “pull it off”. But it also works as a study of power dynamics of an elite investment bank, where the crisis acts as a stressor that brings to the front the internal motivations and moral character of the people that chose to work in the industry.

The notable comparison piece about the financial crisis is Adam McKay’s “The Big Short”. Having a clear progressive bent, McKay uses caustic humor to project his outrage of the crisis in a (albeit funny) political rant. The bankers are caricatured as cartoonishly evil, lacking depth or interiority. The guilty party is clear. We’re here to vent our frustrations and by the end laugh at their stupidity. J.C. Chandor however seems interested in showing the banker’s perspective and probing the their motivations and the rules of their society. Toning down the performances and sharing their perspective, we’re freer to explore their motivations and understand their situations.

The film begins with the discovery of the spoiled assets by an analyst Peter Sullivan (Zachary Quinto) and then a progressive escalation up the management chain. Peter is a young earnest analyst that’s the most naive and out-of-place in the film. He is the most moral and sentimental, and executes his work diligently largely oblivious of the social dynamics that play out around him. His direct coworker, the junior analyst Seth pulled straight from college fits more naturally due to his narrow obsession with his superior’s compensation.

The trading floor manager Sam, the main objector to the plan, does not raise moral concerns, rather he operates under traditional rules of selling that fails in the current crisis. A code of ethics where “we sell only when we know people come back for more” failing to realize that during the impending economic collapse, it’s better to save your hide and screw the other guy over. Sam’s supervisor Jared Cohen (Simon Baker) succeeds where Sam cannot. Dispassionate from other’s problems, he makes calculated economical moves upwards in his career willingly scapegoating his conspirator Sarah Robertson (Demi Moore) when a fall guy is necessary.

Eventually the crisis arrives at the board room where the CEO John Tuld (Jeremy Irons) commands the space. His speeches are theatrical and the board room gives him a chance to play off others and command authority over his ambitious, scheming subordinates. He’s the apotheosis of the establishment, a human manifestation of competitive ruthlessness.

The film stays from the perspective of insiders of the firm. The ramifications of their actions are implied but withheld from our perspective. Their ethical pontifications therefore seem more abstract and theoretical. As Seth mentions glibly “I push numbers around on a computer screen.” The abstraction is the point, insulating them from the broader economic consequences and making their decision-making feel amoral. Tuld takes a historical perspective. The economy moves in cycles, and his actions are purely reactionary. If there is no consequence to your actions, why not get rich?

Everyone has their excuse for why they need the money, Will spends what he makes, Sam is going through a divorce, Eric has a family and a mortgage. These restraints are ultimately self-imposed, they could live more conservatively, downsize their homes, etc, but they all were allure of more money or an ego that wouldn’t accept compromise.